The iconic star Betelgeuse, part of the constellation Orion, is one of the brightest stars visible from Earth and one of the most frequently observed celestial objects in the night sky. But it may not be the only one.

A new theoretical study suggests that Betelgeuse has a Sun-like companion orbiting the star that could be responsible for the star’s puzzling, periodic brightness.

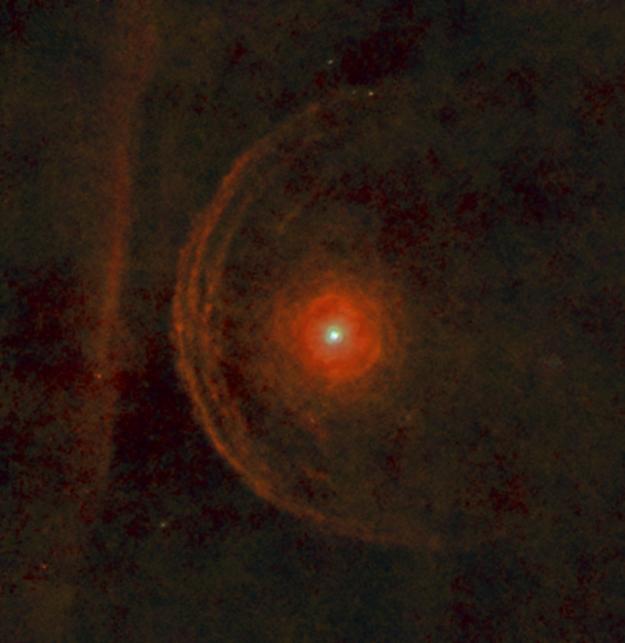

If you point a telescope at Betelgeuse for weeks, you will see it dim, then brighten, then dim again. These pulsations stretch over about 400 days, although the 2020 “Great Eclipse” event shows that such periodicity can sometimes go wrong. But if you were to plot Betelgeuse’s luminosity over years, you would see these 400-day heartbeats overlaid on a much larger, slower heartbeat. Technically called a long secondary period (LSP), this second type of heartbeat lasts about six years, or 2,170 days, in the case of Betelgeuse.

“There are many stars that show LSPs, but most of them do not look like Betelgeuse: most of them have lower masses,” Meridith Joyceassistant professor at the University of Wyoming and co-author of the new study, told Live Science by email.

Periodic changes in a star’s brightness typically occur as the star swells and then contracts, over and over again. This happens because gas near the star’s core becomes superheated and rises to the surface, where it expands ― making the star larger ― but then cools and sinks back to the interior, making the star smaller. The general consensus among astronomers is that Betelgeuse’s 400-day pulsations arise from such cycles. But the cause of the star’s 2,170-day LSP has remained elusive, despite several possible theories, including the presence of giant dust clouds.

Related: Some of the oldest stars in the universe are hidden near the edge of the Milky Way — and they may not be the only ones

The astronomers investigated a range of phenomena that could generate large, slow pulsations in brightness. These included differences in the rotation rate of the star’s core relative to its surface, as well as sunspot-like starspots created by Betelgeuse’s chaotic magnetic fields, driven by electrically conducting fluids within the star.

Ultimately, only one scenario can explain all of Betelgeuse’s parameters: a companion star plowing through the dust clouds shrouding Betelgeuse.

According to the team’s hypothesis, when the companion star — which Joyce calls “Betelbuddy” — comes into view from Earth, it temporarily disperses the dust clouds surrounding its partner. Because this dust normally blocks Betelgeuse, its absence makes the star appear brighter from Earth’s vantage point.

The team’s calculations suggest that Betelgeuse’s friend is much larger than a planet, possibly twice as large as the sun. However, Joyce said that’s not conclusive; she personally believes Betelbuddy is a neutron star, the ultra-dense core of a collapsed star. In that case, “we would expect to see evidence of this with X-ray observations, which we don’t have,” she said.

While no previous studies have suggested that Betelgeuse has a companion, Joyce said it’s not entirely unexpected given the statistics; most stars have one, or even two, sidekicks. Still, verifying this prediction will require direct observations of the binary companion, which can be difficult with current technology. Nevertheless, “Joyce and her team are putting together a few observational proposals. … The first window of opportunity is this coming December.”

The studythat has not been peer-reviewed is available as a preprint on the arXiv server.