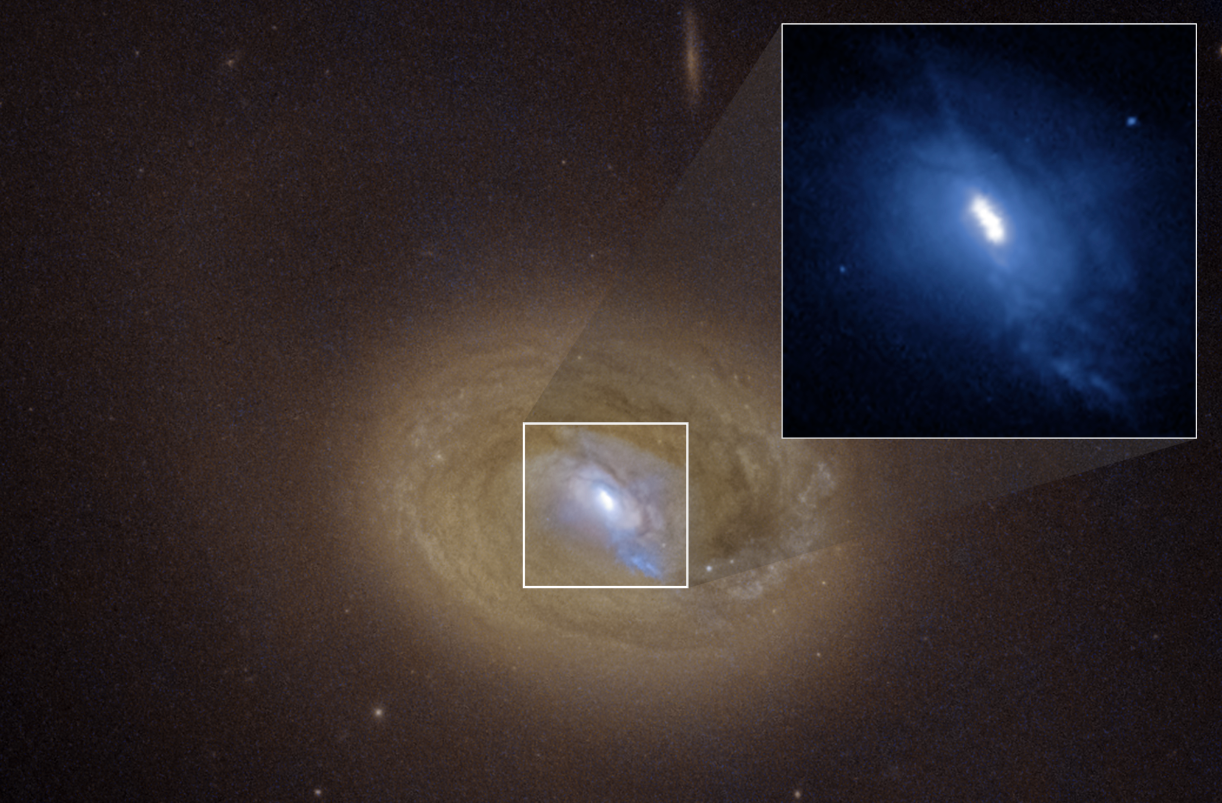

It’s the ultimate telescope vs. supermassive black hole tag-team match as NASA’s Chandra and Hubble team capture a supermassive black hole pair! Not only was this black hole tag team surprisingly close to Earth, but they were also incredibly close to each other!

The supermassive black holes are located in the merging galaxies MCG-03-34-64, about 800 million light-years away. They are only 300 light-years apart.

That’s not all. These two black holes are actively consuming gas and dust that is falling toward them from their surroundings, fueling bright emissions of light and powerful outflows, or jets. Such regions are called “active galactic nuclei,” or “AGNs,” and they can often be so bright that they outshine the combined light of every star in the galaxies around them.

Despite being an almost incomprehensibly large distance from Earth, this pair is still the closest pair of AGNs seen in multiple wavelengths of light. Hubble observed it in visible light, and Chandra saw it in X-rays. A pair of supermassive holes closer than this have been discovered, but it has only been detected in radio waves and has not been confirmed in other wavelengths, according to NASA.

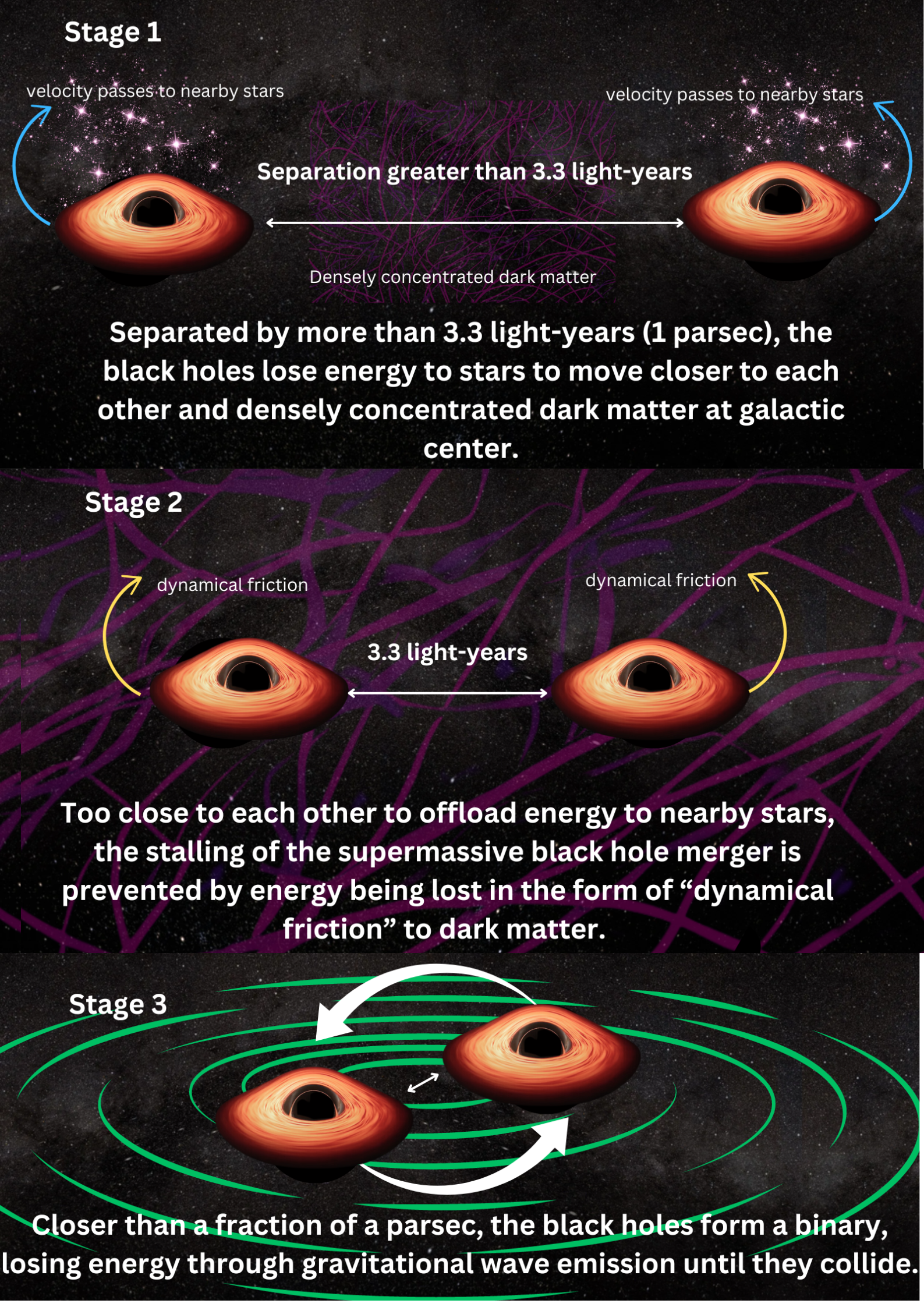

The supermassive black holes at the heart of MCG-03-34-64 are also closer together than the inhabitants of previously discovered binary stars of this type. They would both have been at the centre of their own respective galaxies at one time, with a collision and merger between those galaxies bringing them closer together.

The two supermassive black holes won’t stay as far apart as this one either. As they swirl around each other, the binary system will send out ripples in spacetime called “gravitational waves.” As these gravitational waves circulate through space, they carry angular momentum away from the black holes, causing them to pull toward each other faster and faster, emitting gravitational waves.

This will take about 100 million years, until the supermassive black holes are so close together that they are overwhelmed by their immense gravity and forced to collide and merge, just as their parent galaxies once did.

Related: Tiny black holes could be playing ‘hide and seek’ with elusive supermassive black hole pairs

AGN binaries like this one are thought to have been common in the early Universe, billions of years ago, when mergers between galaxies were more common. This pairing offers a unique opportunity to observe such a binary much closer to home than those that existed billions of years ago, and are therefore billions of light-years away.

Hubble is lucky

This discovery is an example of how serendipity can play a role in astronomy. Hubble discovered the AGN in data that showed a dense concentration of oxygen in a very small region of MCG-03-34-64.

“We didn’t expect to see anything like this,” team leader Anna Trindade Falcão of the Center for Astrophysics|Harvard & Smithsonian said in a statement. “This image is rare in the nearby Universe and told us that something different is going on in the galaxy.”

To unravel the mystery surrounding the events at MCG-03-34-64, Falcão and his colleagues enlisted Chandra to investigate the same area, this time using X-rays.

“When we looked at MCG-03-34-64 in the X-ray band, we saw two separate, powerful sources of high-energy emission that coincided with the bright optical points of light seen with Hubble,” Falcão continued. “We put these pieces together and concluded that we were probably looking at two closely spaced supermassive black holes.”

The team didn’t stop there. They enlisted some help for this space telescope tag team in the form of archival data from the Earth-based Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA) near Socorro, New Mexico. This revealed that the supermassive black hole pair at the heart of this AGn is also emitting powerful radio waves.

“When you see bright light in optical, X-ray and radio wavelengths, you can rule out a lot of things, leading you to the conclusion that these can only be explained by nearby black holes,” Falcão continued. “When you put all the pieces together, you get a picture of the AGN duo.”

Hubble spotted a third bright source in the AGN, which remains somewhat mysterious. The team suggests that this could be gas that has been “shocked” by a high-velocity jet of plasma launched from one of the supermassive black holes, almost like a jet of water from a garden hose blowing away a sand dune.

The findings prove that even after three decades in space, Hubble continues to produce groundbreaking science results.

“Without Hubble’s amazing resolution, we wouldn’t be able to see all this detail,” Falcão concluded.

The team’s research was published Monday (Sept. 9) in The Astrophysical Journal.